In this article, we talk to Thomas McKillop, Special Counsel specialising in Construction and Infrastructure at Thomson Geer, about the scenario all parties want to avoid – construction litigation – specifically around construction defects in commercial and infrastructure projects.

Construction disputes in Australia typically fall into one of three categories: disputes around time, cost and quality. Here, we take a deep dive into quality – an area where solicitor Thomas McKillop says that 99% of disputes involve construction defects or allegations of defective work.

“There can be disputes around whether alleged defects are actually defective according to the construction contract,” Thomas said. “But the most common disputes relate to responsibility for defects. For example, there’s a hole in a wall, a cracked concrete slab, or water ingress. It’s difficult to say those things do not amount to an actual defect – but there are typically questions around the chain of responsibility. The builder might ultimately be responsible to the client, but will usually seek to close the risk gap by assigning blame to the relevant subcontractor or trade, or a subcontractor who was working adjacent to the area and potentially caused the issue.”

Quality evidence is the key (to winning and keeping costs down)

Thomas says that for both the owner and the builder, tracking defects systematically makes sense for two reasons:

- It is more likely to achieve a good quality build for the owner and the end users.

- If there are quality issues and a contractual dispute materialises, “From the legal standpoint, nothing is better, and cheaper, than readily-available contemporaneous evidence,” he said.

To put this more simply:

“The party with the most bits of paper tends to win the fight.”

A tale of two approaches

Let’s illustrate the concept of ‘contemporaneous evidence’ by comparing two examples. The defect in question is water leaking through the window on level 10 of a multi-storey building.

Example 1: Correspondence and affidavits

Thomas works on many cases that involve sifting through correspondence to find mentions of a particular defect. Often the defect will be referenced among many other topics in the same email or letter – a “by the way there is a leaking window, have you looked at it yet” type of comment.

Stumbling across references to a particular defect in the context of a massive construction project is unlikely. So the lawyer needs to work harder, and for longer, to find them.

Because project correspondence often only contains passing references to the defect in issue, the evidential gaps need to be closed by obtaining oral evidence from key people. Typically this involves taking witness statements from multiple parties, like the head contractor, the superintendent, employees and so on. “This might take weeks of work to assemble the evidence relating to a single defect,” Thomas said. “It’s inefficient, expensive, and often people can’t fully remember all the details – the quality of the evidence isn’t great.”

Example 2: A systematic approach

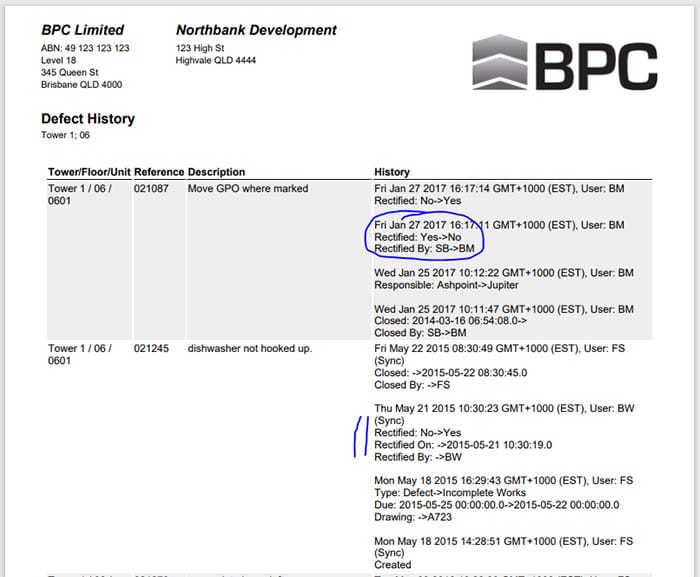

If the builder (or owner) is using specialist construction defect software like ACCEDE to record defects during regular quality inspections, there will be a record of the first time the water leak is noticed – this is a permanent and contemporaneous record of fact. If there is a dispute in six months, or three years, there is no contest about this fact – and there is photographic evidence recorded. This defect remains open until it is communicated with the responsible party, rectified and quality checked. “What you’re left with is a complete evidential story of the defect that you can print out and get into evidence in 10 minutes,” Thomas said.

“From a legal standpoint, we think about documentation – the whole data trail that records the story of the defect across every important date, party and milestone. If there’s a dispute about a defect and one party produces an affidavit years after the fact that’s based on memory – that is evidence – but it will never trump a contemporaneous record of fact produced by a software system designed for recording the existence of defects.”

Benefits for the owner/developer

The owner or ultimate client of the construction project stands to gain in two areas by using software to track defects. Firstly, they are more likely to end up with a better-quality product (and reduce complaints from the end user of the construction). Secondly, if there are quality issues, they are armed with the best possible evidence to convince the builder to return to resolve defects. Often the final defect list is discussed during a meeting towards the end of the defects liability period and prior to the release of final security. “If you go into this meeting with a solid, non-biased, defect report, you’re more likely to come to an agreement faster and avoid a dispute all together,” Thomas said. “And if you do end up in a dispute, you’re armed with excellent evidence that will put you in a better position to negotiate out of it, or win it.”

Benefits for the builder

Legally, tracking defects properly protects the builder in two ways. It provides contemporaneous evidence about the defect itself and its handling. If there is a dispute, the builder can prove the defect was closed and the quality manager accepted its closure. Alternatively, the builder can also follow the defect down the chain to find out which subcontractor caused the defect, and hold it accountable. In these ways, the builder can resolve the problem or otherwise close the risk gap by pursuing the responsible party – while also reducing the costs incurred in doing so.